Oven Bird By Robert Frost

Andrew has a keen interest in all aspects of poetry and writes extensively on the discipline. His poems are published online and in impress.

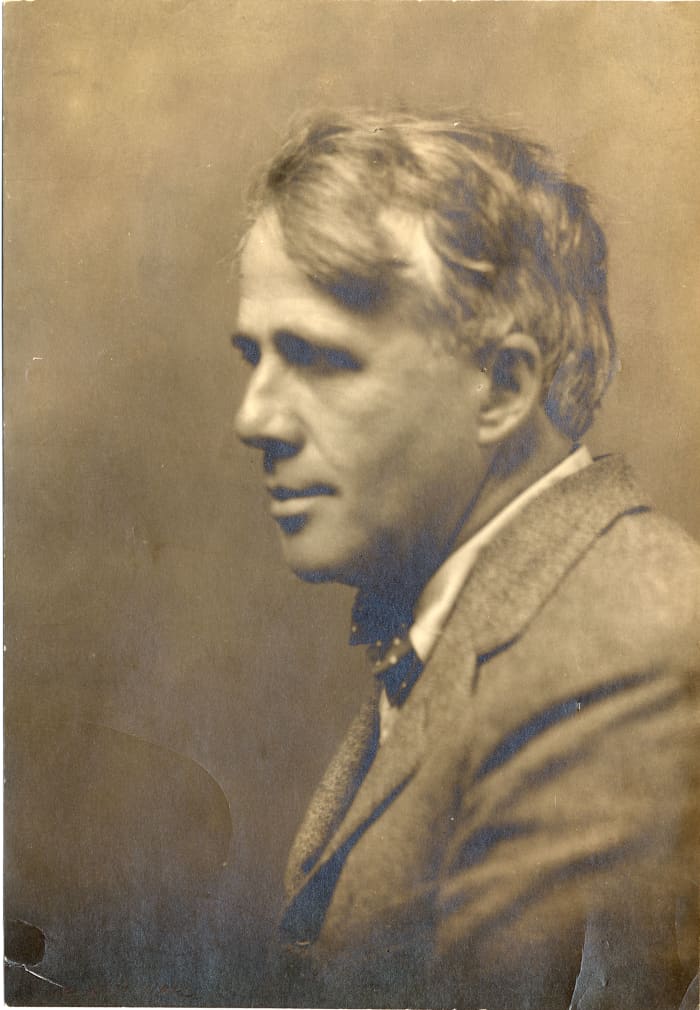

Robert Frost

Summary of "The Oven Bird"

"The Oven Bird" is an unusual sonnet containing an extended metaphor, in which a bird, the Oven Bird, becomes the poet, and vice versa. The vocal of this bird is the piece of work of the poet—shaping linguistic communication into suitable forms, creating designed sound— changing the relationship between nature and language.

Simply how come Robert Frost chose this detail common bird to represent himself equally a middle-anile poet? Could it be that the male's simple, repetitive song, oftentimes described equally 'instructor, instructor, teacher', reminded him of what verse shouldn't be— loud, unchanging and undisguised? In that location'due south the paradox.

Frost published the verse form in 1916 in the book Mountain Interval. He had not long returned from England with his family following the outbreak of the beginning world war, began instruction, and wanted to consolidate his position equally i of the leading modernist poets.

"The Oven Bird" has acquired much controversy over the years. Some call up it is a response to an earlier poem past Mildred Howells, who wrote a sentimental poem titled "And No Birds Sing", which Frost knew of. The first line of "The Oven Bird" could exist a direct counter to this championship: 'There is a vocaliser everyone has heard'.

This association probably holds a grain of truth but Frost then expanded and explored in his own inimitable manner, the nature of diminishment through the song of the ground-abode woodland warbler, known every bit the oven bird.

And it should be noted that Frost had read and admired H.D.Thoreau's groundbreaking volume Walden, which mentions the song of the oven bird: 'the oven-bird's note is loud and unmistakable, making the hollow woods ring.'

However, Frost denied ever being a poet of fauna and flora: 'I am not a nature poet. There is almost always a person in my poems.'

Putting everything together it is impossible not to read "The Oven Bird" and believe that the poem has a strictly literal theme. It is well-nigh poetic creativity and the relationship the poet'southward words have to nature and to life'south processes.

"The Oven Bird"

In that location is a singer everyone has heard,

Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks audio again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to 10.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we proper name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be equally other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to brand of a diminished thing.

Assay of "The Oven Bird"

"The Oven Bird" is a fourteen line sonnet with full end rhymes, a basic iambic meter with anapaests and a tribrach mixed in here and there to vary the speed and rhythm of the lines. For example:

There is / a sin / ger ev / ery1 / has heard, (5 iambs=iambic pentameter)

Is what / to make / of a / dimin / ished affair. (2 iambs+pyrrhic+2 iambs)

The rhyme scheme is: aabcbdcdeefgfg and all are full rhymes which help tightly bind the lines and bring a memorable edge to the verse form.

Although the sonnet looks traditional on the folio—14 lines—it is not your typical Petrarchan sonnet which is carve up into an octet and sestet, the sestet being the turn or answer to the octet's questions and proposals.

Scroll to Continue

Read More From Owlcation

- "The Oven Bird" is split more 10 and four, the first ten lines focusing on the bird's song and the diminishing signs of the seasons, whilst the final four conclude with the reason for its existence.

More Analysis of "The Oven Bird"

Robert Frost comes over as a bit of a trickster in "The Oven Bird". The opening line is a plain if innocent declaration—this songster is known to all because of the loudness and clarity of its vocal. Note the altered stress and syntax of the second line—the inclusion of mid-wood bird fits into the syllabics (ten) only slows the reader down.

Such music pours along from this bird that alliteration is needed in the third line to reinforce the bulletin—solid tree trunks audio—which suggests that this song has more than to it than meets the ear.

Merely what exactly is the message from this bird which builds a dome shaped nest, like an oven? He says, he says, he says . . . this obvious repetition echoes the actual vocal of the male person bird who, in line four, starts to outline the diminishments.

And don't forget that bird=mature male poet, so line four contains the message that fourth dimension is passing for this versifier, his language is maturing, he is no longer a greenhorn and has changed his approach. He has had to respond to the passage of fourth dimension by crafting a certain monotony.

The enjambment of line four allows the reader to keep on to line five, the speaker acknowledging that his energy and freshness are 10 times less now he's reached center historic period and is facing the inevitable fall.

And then the cycle of the seasons affecting the bird and the flowers and the trees is likewise experienced past the speaker who is singing the song of the poet.

- Annotation the paradox: the bird is non singing but proverb which suggests that there is a need for interpretation, but how is it possible to sympathize bird vocal when linguistic communication is forever inadequate?

In line ten, which is pure iambic, the final He says . . . evokes a strong image— everything is covered in dust, dust from the highway. Dust is associated with the ritual of christian burying, as in dust to grit, ashes to ashes, bloodshed, but this particular grit has come up from human-made progress, that all too familiar highway.

Symbolically, the dust is regeneration, both physical and spiritual. Information technology is the stop of things and the beginning, silence and the Word. Nature and humanity cannot escape it for they are function of the whole; they come from the aforementioned natural history.

Frost must take known that the oven bird'south song becomes a plaintive preacher, preacher, preacher co-ordinate to some, but the poem moves away from any religious associations, preferring a philosophical arroyo, closer to Darwinian thinking.

The mysterious and anthropomorphic line twelve implies that the oven bird simultaneously sings and does not, that by opening its bill and pouring out its heart it is unemotional but tin move a human being, especially a poet, and inspire fresh language.

What I think the speaker ways is that at present the summer has almost passed in that location is no longer whatever demand to sing, things are diminishing so why waste energy on a full-blown song? The season is changing and with it the song of the bird. I also think at that place is some subtle adoration for the bird's unique noesis/instinct.

With Frost nosotros know the bird represents something other than a bird—there is a parallel with the poet himself, having reached a certain phase in his own creativity, and asking the question of his own possible diminishment. And it'southward possible to take information technology a stage farther and say that this process applies to all creative types?

This sonnet does non have a solid answer, there is no definite conclusion but merely a question—what to make of a diminished affair—the bird's song an instinctive expression of existence, the poet's words an uncertain and sensitive attempt to frame 'momentary stays confronting confusion.'

Sources

The Hand of the Poet, Rizzoli, 1997

www,poetryfoundation.org

www.poets.org

© 2017 Andrew Spacey

Oven Bird By Robert Frost,

Source: https://owlcation.com/humanities/Analysis-of-Poem-The-Oven-Bird-by-Robert-Frost

Posted by: merrittwenctim.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Oven Bird By Robert Frost"

Post a Comment